One fantastic organization that has worked with us hand-in-hand and arm-in-arm in Haiti ever since the earthquake of January 2010, is the American Joint Jewish Distribution Committee, or the JDC as its more commonly referred to.

What follows is a story recently penned by one of their medical volunteers from London, as she reflects on her time spent working in Haiti following the earthquake, and how the experiences changed her.

It’s a very personal account, quite moving and is written from her heart.

DW HHI

DON’T CRY IN HAITI

By Vered Schimmel-Lifschitz

Can it really be one year and 10 months since I left Haiti? Every day, I have been longing to return.

Every picture tells a story, and with the story I was again flooded with a passionate desire to return.

There have been other disasters. Why did this particular disaster have such an exceptional pull on my heart? Maybe because the people of Haiti have suffered so much already. Why should they, of all people, be struck by this additional tragedy?

The compound we stayed in was so much more than the basics we had expected. Even in the midst of disaster, we were treated like welcome guests. We were given the most heart warming welcome by the Heart to Heart team and were introduced to the American doctors, nurses and a paramedic whom we were to get to know so well in the coming days.

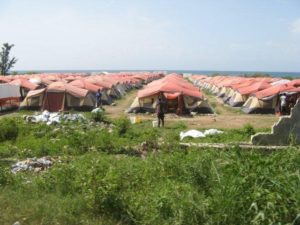

Downtown in the Bel Air neighbourhood, in a three-story church building, which had miraculously survived the earthquake and overlooked the port and shattered city, we found 200 quiet, stoic patients waiting for us. Young and old, babies, the sick and injured, many in pain, sat in well organized rows, waiting in a civilised, orderly fashion for medical treatment.

We spent the next day out of the city in Leogane. This town was at the epicentre of the earthquake and had suffered massive damage. Everywhere we looked there was nothing to see except piles of rubble lying amongst the wreckage of houses.

How much good did we do? Was it just a tiny drop in a vast ocean? Is it possible to care for so many sufferers? I knew I would break down at some point because the scale of the human disaster was so overwhelming. To witness destruction on that epic scale, to see so many people displaced, to see so much injury, pain and misery, was simply shattering. You cannot witness such things without being touched and transformed yourself.

One of our patients on my first day in Port-au-Prince was a young woman suffering from a partly open and infected caesarean section. She had walked to our clinic for over an hour in the heat, two days after her C-Section had been performed and botched. She had no access to any other hospital and had come to us as a last resort.

We treated her as best we could, cleaning the wound and giving her antibiotics, with instructions to come back to see us in three days time. When she returned, the wound was still in poor condition and it was then that we found out that she had lost her baby. Our interpreter advised her to come back again. It was when this young woman left us that it really hit me.

I could not hold back my tears any longer. Hurrying through the crowds of patients and team workers, I hastened up the stairs to the damaged open roof area overlooking a vast sea of misery, and sobbed.

Yet my tears were of no use to anyone but myself. Tears were a luxury no one could afford in Haiti. I knew I had to pull myself together and rejoin the others. On the way back I was stopped by George, our dear, kind translator. Gently he barred my way, asking if I was OK and refusing to let me pass. “Sure”, I replied, anxious to show that I was fine. George knew better, and insisted on comforting me and looking directly into my tear-filled eyes he said something I shall never forget: “Don’t cry in Haiti. We must believe in God and be strong and continue in hope and belief.”

So there I was, flooded in tears, being consoled by a young Haitian whose whole world lay shattered in ruins around him. George taught me a valuable lesson, to get my act together, offer all I had and continue to give whatever I could.

Back at home, surrounded by the dull London weather and the home comforts we take for granted, the memory of my two weeks in Haiti refuses to fade. Having seen the devastation and misery first hand, is it not our obligation to do so much more to help? Of course I recognise that there are so many other poor and devastated countries around the world but Haiti is a place where we could not only give temporary relief, but also make long-term changes. We could give the Haitian people opportunities, steps towards a better future, for them and their children.

###